Summary

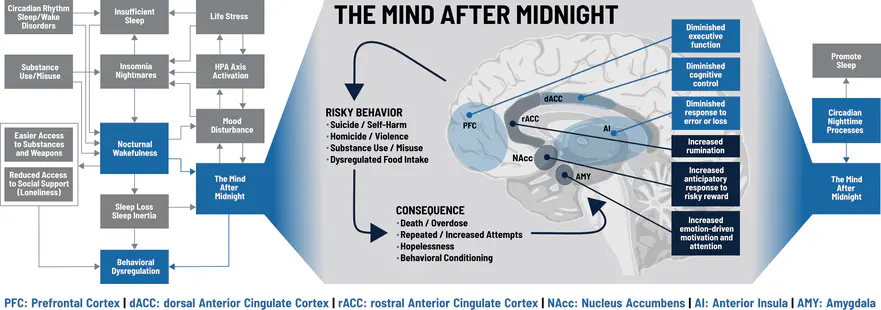

The Mind after Midnight is a neuroscience-driven hypothesis about how sleep and circadian rhythms influence dysregulated human behaviors. The hypothesis was first published in Frontiers in Network Physiology. The core concept is that nocturnal wakefulness produces impaired neurocognition that increases risk for dysregulated behaviors.

Nocturnal Wakefulness

Nocturnal wakefulness means being awake when you haven’t had enough sleep and when your circadian rhythm expects you to be asleep.

- Sleep is a process that restores our brain (and body) to normal operations. When we’re awake, the brain uses energy to do cognitive work. Eventually this produces cognitive fatigue such that our brains don’t work as well anymore. This is called “sleep pressure”, and the only way to relieve it and get our brain back to working right is to sleep.

- Circadian rhythms refer to the roughly 24-hour cycles that connect our biology and behavior to the light/dark cycle of earth. Circadian rhythms are organized by specific parts of our brain.

- When we’re supposed to be awake, our circadian rhythms are in an upstate that promotes wakefulness and cognition to help us do our jobs and stay alive. For most people this is during the day.

- Because we need to sleep, there are also times when our circadian rhythms enter a *downstate to promote sleep by reducing wakefulness and cognition. For most people, this is at night.

- NOTE: Circadian rhythms are strongly influenced by light (or lack of light), but can actually be adjusted or even inverted. If you’ve ever traveled across a few time zones, you’ve felt this “jet lag” as your circadian rhythm adjusts to the new light/dark cycle. Shift workers, for instance, can train their circadian rhythm to promote wakefulness at night and sleepiness during the day. For the purpose of the Mind after Midnight Hypothesis, we are concerned with wakefulness during the typical sleep period, or the downstate.

Impaired Neurocognition

Nocturnal wakefulness involves multiple hypothesized changes in neurocognition, including emotion regulation, reward processing, and executive function.

- Emotion regulation involves sensory perception (“what do I see?”) and salience assignment (“what does it mean?”). Emotional meaning is derived from two separate but closely related systems: positive affect and negative affect.

- Negative affect is generally steady throughout the day, but peaks sharply at night.

- Positive affect is generally increases during the day and decreases at night.

- Consequently, nocturnal wakefulness results in wakefulness and cognition when the cognitive systems of negative emotion are increased and positive emotion are decreased.

- Reward processing involves systems of reward/motivation and punishment that guide decision-making. Preliminary evidence suggests these systems are skewed at night.

- Response to a reward (e.g., food, money) varies across the day, with the greatest responses occurring during the afternoon (during the peak in positive affect).

- When sleep deprived, the brain may overestimate the reward and underestimate the cost of a risky decision. This may promote risky behaviors while diminishing sensitivity to negative feedback.

- Executive function refers to multiple complex processes that guide our behavior. Sleep- and circadian-dependent changes in the brain during nocturnal wakefulness:

- Preferentially affect the prefrontal cortex, where executive functions are housed.

- Impair working memory, complex attention, and problem solving.

- Decrease behavioral inhibition and impulse control.

- Make decision-making inflexible and skewed toward high-risk, high-reward, net-loss decisions.

Dysregulated Behaviors

Dysregulated behaviors reflect efforts to meet biological (or more often, psychological) needs in ways that are ultimately harmful. Although any number of behaviors may fall under this rubric, the main examples we examined are suicide/self-harm, homicide/violence, substance use, and dysregulated food intake.

-

Multiple studies (many detailed on this website) highlight a connection between nocturnal wakefulness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

-

- Perlis et al. 2016: A study of suicides from the National Violent Death Reporting System (2003-2010) to evaluate the standardized incident risk for suicide after adjusting for population wakefulness. Although suicides peaked in incidence around noon, the standardized incident risk was highest at night (12am-6am) when adjusted for population wakefulness.

-

- Tubbs, Perlis et al. 2020: A follow-up analysis of the NVDRS suicide data (2003-2010) to evaluate the nocturnal risk for suicide across months and methods of suicide by multiple demographics groups. The population-wakefulness adjusted risk of suicide remained highest at night and did not vary by month or method of suicide. The analyses are detailed here.

-

- Tubbs, Fernandez et al. 2020: An analysis of sleep/wake timing among roughly 1000 adults in the Philadelphia area in relation to suicidal ideation. Individuals who reported wakefulness between 11pm and 5am were more likely to report suicidal ideation. The analyses are detailed here.

-

- Tubbs, Harrison-Monroe et al. 2020: A case report of a patient with schizoaffective disorder who was undergoing actigraphic monitoring when he attempted suicide. Actigraphy data show that, two days before he attempted suicide, he inverted his sleep schedule such that he slept during the day and was awake at night. COnsequently, he was awake at a time his brain expected him to be asleep.

-

- Tubbs, Fernandez et al. 2021: An analysis of sleep/wake timing and suicidal ideation in the NHANES from 2015-2018. Individuals who reported wakefulness between 11pm and 5am were more likely to report suicidal ideation, while those with wakefulness between 5am and 11am were less likely to report suicidal ideation. The analyses are detailed here.

-

-

Homicide and violent behavior may also increase in incidence during nocturnal wakefulness.

-

Preliminary evidence suggests patterns of substance abuse may change at night.

-

Preliminary evidence suggests nocturnal wakefulness leads to food intake based on hedonic reward rather than nutrition, which may lead to dysregulated food intake.